Fall/Winter 2019 issue

There are students whose life experience helps make a classroom thrive. Who, when filling out their university applications, could have used an extra page or two to even begin to describe the depth of their life experience. Here are just a few of them.

These are four special stories of four special people who came at university from various angles, and different ones than most. Their presence made everyone think a little longer, and learn a little more.

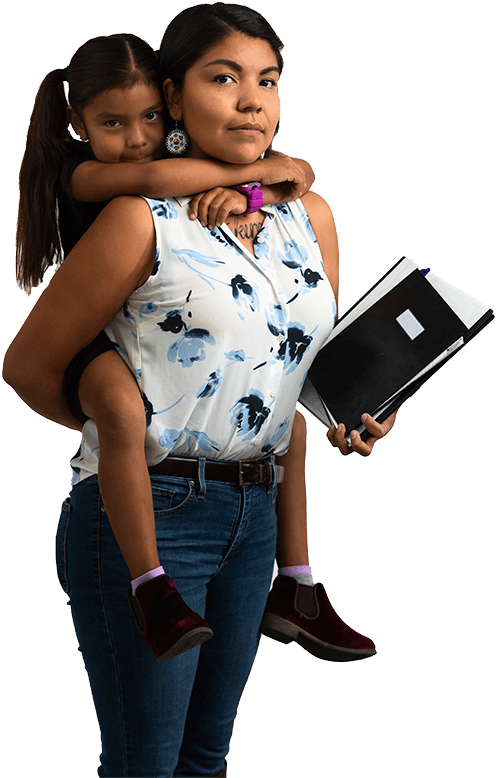

Latasha Calf Robe

Bachelor of Business Administration — General Management, 2017

For Latasha Calf Robe, the very thing that made some people see her as an undesirable student and classmate was actually what drove her success in university: motherhood. The same year Calf Robe was accepted into the business program at Mount Royal she gave birth to her first child.

She found she related to the course material better because she was a parent. “Lots of the theories we talked about in class I was living in my life. There was a lot of the unexpected and lots of rolling with it and trying to plan as much as you could and being okay when things went a little sideways.”

“Lots of the theories we talked about in class I was living in my life.” — Latasha Calf Robe

But her classmates didn’t often see the advantage, she recalls. “In class, I was usually divided by being the only Indigenous student and if it came up that I had children it was an even bigger divide. People wouldn’t always want to work with me or they assumed that I didn’t have time.”

By her final year, Calf Robe connected with mature or international students — others who could relate better to her circumstances.

Calf Robe was among a small group of students with children who benefited from Indigenous family housing on campus, a program that was recently bolstered by a donation from David and Leslie Bissett. But housing, policies and attitudes remain obstacles for many student parents, she notes.

“Mandatory attendance should be reconsidered. Having a sick child at home and no one to help you, is a real barrier.” Emergency childcare on campus would also be a huge help, she adds.

Calf Robe was allowed to bring her sick baby with her to an exam, which is the kind of accommodation she hopes will become more common if people can “move away from the assumption that children can negatively impact things. Having children helped to give my education purpose. Without my children, I wouldn’t be where or who I am today.”

In 2017, the year she graduated with a business degree, Calf Robe received the Calgary Aboriginal Youth Achievement Award. She now works on campus at Mount Royal's Institute for Community Prosperity and the Trico Changemakers Studio.

Mark Fuchko

Bachelor of Arts — History, 2016

When Cpl. Mark Fuchko started his Bachelor of Arts in history at Mount Royal in 2011, the army vet had a bit of trepidation about being in the classroom after serving for almost a decade in the Canadian Armed Forces.

His experiences were different from most students. He had served two tours in Afghanistan and during his second tour, Fuchko narrowly survived the explosion of an improvised explosive device.

“There were times when I thought things were very trivial because it’s really hard to find meaning after you’ve gone to these places,” Fuchko says.

After enlisting as soon as he finished high school, Fuchko was deployed for a nine-month tour of Afghanistan in 2005. Struck by the poverty and hardship Afghans suffered, Fuchko says, “I remember coming back to Canada and just feeling this immense sense of pride, and lucky that I was born here.”

In 2008, he was redeployed for a second tour of Afghanistan. That was when his life changed forever.

Fuchko was part of a cordon and search operation just outside of Kandahar, looking for foreign fighters, weapons caches and bomb-making materials. On the way out of the area, the vehicle behind his got stuck in the mud. Fuchko reversed his own vehicle to help tow his fellow soldiers out.

“There were times it was physically challenging because I can’t sit really well. I can’t stand really well. But I wanted to be there every day. I wanted to be at every single class. I wanted to listen to what my profs wanted to say. I really wanted to put in an effort and I had a lot of drive there.” — Mark Fuchko

“As I was towing, I actually sank deeper into the mud and I struck this huge improvised explosive device,” he says. “When the bomb went off, there was this huge flash and this loud ‘ping’. And I remember saying, ‘Uh oh, that can’t be good.’ And then I remember looking down and my right foot was actually sitting in my lap. And I remember saying something like, ‘Oh man, if I die here, my mom is gonna kill me.’ And I knew right away that I was hurt.”

Thrown so hard that he also broke his pelvis in several places, Fuchko couldn’t feel his left foot. He bent down to tap his boot. A bone came out of his pant leg.

Trapped in the wrecked vehicle, he was forced to tourniquet his own legs. With the smell of the homemade explosive filling his nostrils, all he could think about was getting out so he could die in the open air.

He waited in agony for 45 minutes until his comrades managed to extract him. He was placed in an air ambulance and flown to a military hospital in Germany. The bones in his legs were ruined … medical staff had to amputate both below the knee.

“I remember thinking my life was over,” Fuchko says.

Fuchko spent time recovering at the Glenrose Rehabilitation Hospital in Edmonton, which specializes in treating injured soldiers. Just over three months after his injury, he was walking on artificial limbs. A peer support network — found through the Soldier On program, which connects veterans and serving members through sport — was key to his recovery.

“That really helped me get back on my feet, to develop that core group of friends who were going through the struggle together,” Fuchko says. “And it’s been a struggle. I got hurt 11 years ago. And they always tell you when you deploy that if you get hurt, you’ll be taken care of forever. And this is, in fact, false.”

Fuchko says he’s not upset about what happened to him in Afghanistan — he joined the military knowing the risks. But when he came back to Canada and had to deal with hurdles in the system to access compensation for his injuries, that’s when he felt angry and betrayed.

“I’ve had to prove that my legs are missing more than once,” he says.

In his last years of service, he was posted to The Military Museums, educating visitors about military life. In 2011, he enrolled at Mount Royal, just across the street.

It was easy to meet people at Mount Royal, and his professors were supportive, Fuchko says. “I didn’t feel like I was just this number getting processed. I felt like they actually cared about my opinion, what I had gone through and how I was interpreting material, and my own knowledge and my own philosophy that I brought into the classroom.”

Fuchko retired from the military in 2014, and completed his degree in 2016. After graduating from MRU with a history degree, he earned a Bachelor of Education from the University of Calgary with the hopes of teaching part time.

He says he doesn’t know what the future will look like. His health has declined over the past few years and he’s navigating a new benefits package from Veterans Canada.

“If my benefits lay out the way I’m hoping they do, I wouldn’t mind just teaching part time because at least I can contribute something as my goal is not to sit around at home,” Fuchko says. “Sometimes that’s unfortunately what I have to do.”

While it’s been difficult to adjust to post-military life, Mount Royal was a key part of the transition.

“It gave me something meaningful to do that was intellectually challenging,” he says. “There were times it was physically challenging because I can’t sit really well. I can’t stand really well. But I wanted to be there every day. I wanted to be at every single class. I wanted to listen to what my profs wanted to say. I really wanted to put in an effort, and I had a lot of drive there.

“And I think that really encouraged me to move on from being a broken soldier and into a new part of my life.”

Maryam Yaqoob

Bachelor of Science — Cellular and Molecular Biology, 2017

In 2008, Maryam Yaqoob was a refugee.

In 2017, Yaqoob was the valedictorian of her class of 216 graduates at MRU.

Yaqoob was born and raised in Mosul, Iraq, until targeted attacks against Christians forced her and her family from their home. One evening, she was doing homework when her parents said they had to leave. Right then. She grabbed some clothes and textbooks and they fled to a monastery in the north of Iraq that had been set up as a camp for religious refugees. After living there for a few weeks, Yaqoob’s family rented an apartment in Kurdistan, and then moved to Damascus, Syria, in 2009.

She never saw her home again.

“My drive to obtain an education mainly comes from the difficulties that I faced growing up.” — Maryam Yaqoob

With assistance from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Yaqoob’s family came to Canada in 2011, which made them “over the moon happy.” But the transition was not easy, she says. “As refugees, we knew little to no English, had no financial support and didn’t have any friends or family.”

Despite those barriers, Yaqoob excelled in high school, earning marks in the 90s. In 2013, she was accepted to Mount Royal, supported by academic scholarships, and she became a Canadian citizen in 2015.

“My drive to obtain an education mainly comes from the difficulties that I faced growing up. My education quality went downhill when we were internally displaced in 2008 and while in Syria. I had to start over every time we were displaced: making new friends, learning a new language and adapting.”

Yaqoob was named to the President’s Honour Roll for each of the four years of her undergraduate degree, was invited into the Golden Key International Honour Society’s Mount Royal chapter — reserved for the top 15 per cent of students —and was the recipient of the Centennial Gold Medal at graduation. She was subsequently accepted to the University of Calgary’s Cumming School of Medicine and plans to work as a physician, with hopes of serving marginalized populations.

Refusing to define herself by her past, Yaqoob says she is glad to have been able to provide perspective on the “real refugee.”

“To some people, they think refugees coming in are just a burden on the economy. What people don’t realize is the economic, social and community rewards that follow. Refugees don’t stay refugees forever, they become citizens and contribute to Canada, join its armed forces, pay taxes and defend its values. It took me less than two years to start working and paying taxes. I no longer define myself as refugee. I am much more than that.”

Yaqoob says she succeeded because she didn’t dwell on her hardships, and that anyone can have disadvantages shaped by their experiences. “What’s important is to recognize your disadvantages, be kind to yourself and persevere.”

John Ross Ackerley

Music Performance Diploma — Jazz, 2010

“The upright bass case is the best sleeping bag,” John Ross Ackerley says.

Owing to financial hardship and other circumstances, Ackerley was homeless throughout his time at Mount Royal. However, he wouldn’t let not having a roof stop him from pursuing his passions and completing his education.

As an obsessive musician and jazz student, Ackerley found himself safe in the unoccupied classrooms of Mount Royal, plucking the bass as he drifted off to sleep.

“(Education is) a real gift, and it can offer a lot to so many different people.” — John Ross Ackerley

“I’m paying money to be in this school, and I’m using this time to learn — so, why can’t I be here and practise?” he says of how he felt. Ackerley spent many, many hours rehearsing to be a great musician, and excelled in his classes. But he is now hesitant to romanticize the culture of over-practising in music, or over-working in life.

“I valued it so much to where it was kind of unhealthy, but I was also validated by my peers,” Ackerley remembers. He now thinks a better way to approach trying to become a virtuoso is with “perspective and humanity.

“Take care of yourself and other people that are trying to do it.”

After his time at the Mount Royal Conservatory, Ackerley completed his Bachelor of Music — Jazz Studies at Vancouver Island University, and then went on to complete a Bachelor of Education — Special Education at the University of Regina.

He now works as a behavioural autism interventionist, and is motivated to address systemic challenges and promote inclusivity in educational settings. Ackerley is adamant that schools should open doors and foster opportunities for those with challenges affecting their education, including lack of funds.

“(Education is) a real gift, and it can offer a lot to so many different people.”

Read more Summit

Breaking down barriers

Everyone's path to Mount Royal is unique, with each student reaching or surpassing benchmarks and overcoming obstacles to eventually land on campus.

READ MORE