Mount Royal University is situated on an ancient and storied land steeped in ceremony and history that, until recently, was occupied exclusively by people indigenous to this place. With gratitude and reciprocity, Mount Royal acknowledges the relationships to the land and all beings, and the songs, stories and teachings of the Blackfoot, the Tsuut’ina, the Îethka Stoney Nakoda and the Métis.

During the verbal negotiations for Treaty 7, the Nations understood that the land would be shared and that a cooperative relationship would be built to last “as long as the grass grows, the sun shines, and the rivers flow.” The Nations of the Treaty were the Siksika Nation, Piikani Nation and Kainai Nation of the Blackfoot Confederacy, as well as the Tsuut’ina Nation and the Chiniki, Bearspaw and Goodstoney Nations of the Iethka Stoney Nakoda. However, verbal promises made to these First Nations by the Crown and the Canadian government were not reflected in the written version of Treaty 7, and many promises that were included in the written version have been broken.

What followed were policies of cultural genocide and assimilation that caused profound harm. The original people of these lands were confined to reserves, prohibited from pursuing traditional practices and forced to send their children to residential schools. Rather than building meaningful and mutually beneficial relationships, there was dispossession and exploitation in systems of economic and social marginalization.

As such, Mount Royal University is committed to advancing the success of Indigenous learners and respectfully supporting Indigenous cultural identities and integrity, leading to a good life in all its aspects. Mount Royal will challenge settler colonialism and systemic racism and discrimination by addressing the legacy of broken promises and rebuilding the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. This includes those who now live at the confluence of the Elbow and Bow rivers, a place referred to by the Blackfoot as Moh’kinstis, the Tsuut’ina as Guts’ists’i and the Îethka Stoney Nakoda as Wîcîspa. Mount Royal will meet these goals by committing to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action and adopting and applying the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The above-mentioned is Mount Royal’s current institutional land acknowledgement, which was created in 2024 and most recently updated in January 2026. The University published its first land acknowledgement in 2016.

Pronunciation guide

Name of the land situated at the confluence of the Elbow and Bow rivers (referred to in English as the City of Calgary):

Usage guidelines

The Mount Royal University Land Acknowledgement is delivered at formal ceremonies and institutional events, and presented in all major institutional publications (digital, print and online). Events or materials that represent Mount Royal should feature the institutional land acknowledgement in its full format or an abbreviated format (below).

Abbreviated formats

Mount Royal University is situated on an ancient and storied land steeped in ceremony and history that, until recently, was occupied exclusively by people indigenous to this place. With gratitude and reciprocity, Mount Royal acknowledges the relationships to the land and all beings, and the songs, stories and teachings of the Siksika Nation, Piikani Nation and Kainai Nation of the Blackfoot Confederacy, the Tsuut’ina Nation, the Chiniki, Bearspaw and Goodstoney Nations of the Iethka Stoney Nakoda, and the Métis.

As such, Mount Royal University is committed to advancing the success of Indigenous learners and respectfully supporting Indigenous cultural identities and integrity, leading to a good life in all its aspects. Mount Royal will challenge settler colonialism and systemic racism and discrimination by addressing the legacy of broken promises and rebuilding the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. This includes those who now live at the confluence of the Elbow and Bow rivers, a place referred to by the Blackfoot as Moh’kinstis, the Tsuut’ina as Guts’ists’i and the Îethka Stoney Nakoda as Wîcîspa. Mount Royal will meet these goals by committing to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action and adopting and applying the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Recommended for institutional events and gatherings with time constraints or institutional publications with space constraints.

Mount Royal University is situated on an ancient and storied land steeped in ceremony and history that, until recently, was occupied exclusively by people indigenous to this place. With gratitude and reciprocity, Mount Royal acknowledges the relationships to the land and all beings, and the songs, stories and teachings of the Siksika Nation, Piikani Nation and Kainai Nation of the Blackfoot Confederacy, the Tsuut’ina Nation, the Chiniki, Bearspaw and Goodstoney Nations of the Iethka Stoney Nakoda, and the Métis.

Recommended for institutional events and gatherings with time constraints or institutional publications with space constraints.

With gratitude and reciprocity, Mount Royal acknowledges the relationships to the land and all beings, and the songs, stories and teachings of the Siksika Nation, Piikani Nation and Kainai Nation of the Blackfoot Confederacy, the Tsuut’ina Nation, the Chiniki, Bearspaw and Goodstoney Nations of the Iethka Stoney Nakoda, and the Métis.

Recommended for institutional events and gatherings with time constraints or institutional publications with space constraints. This version is also suitable for email signatures or on a website footer.

History of Treaty 7

Negotiated in 1877, Treaty 7 is one of 11 numbered treaties between the Crown and Canadian government and First Peoples across Canada. Covering southern Alberta, it was negotiated at Blackfoot Crossing and involved the Blackfoot Confederacy (comprising the Siksika, Kainai and Piikani), the Tsuut'ina and the Stoney Nakoda.

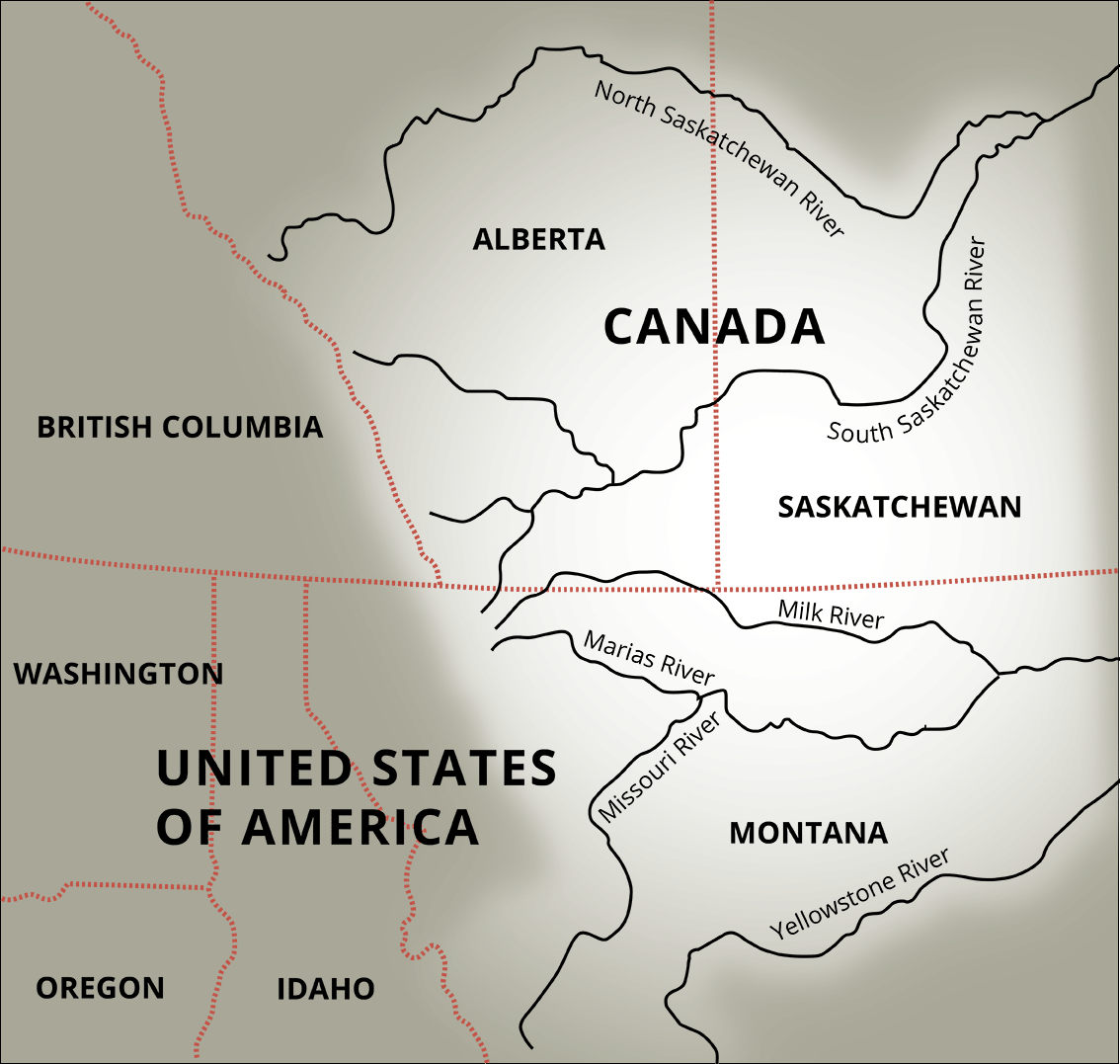

Original Blackfoot territory

This map depicts an approximation of the Blackfoot territories before contact with settlers.

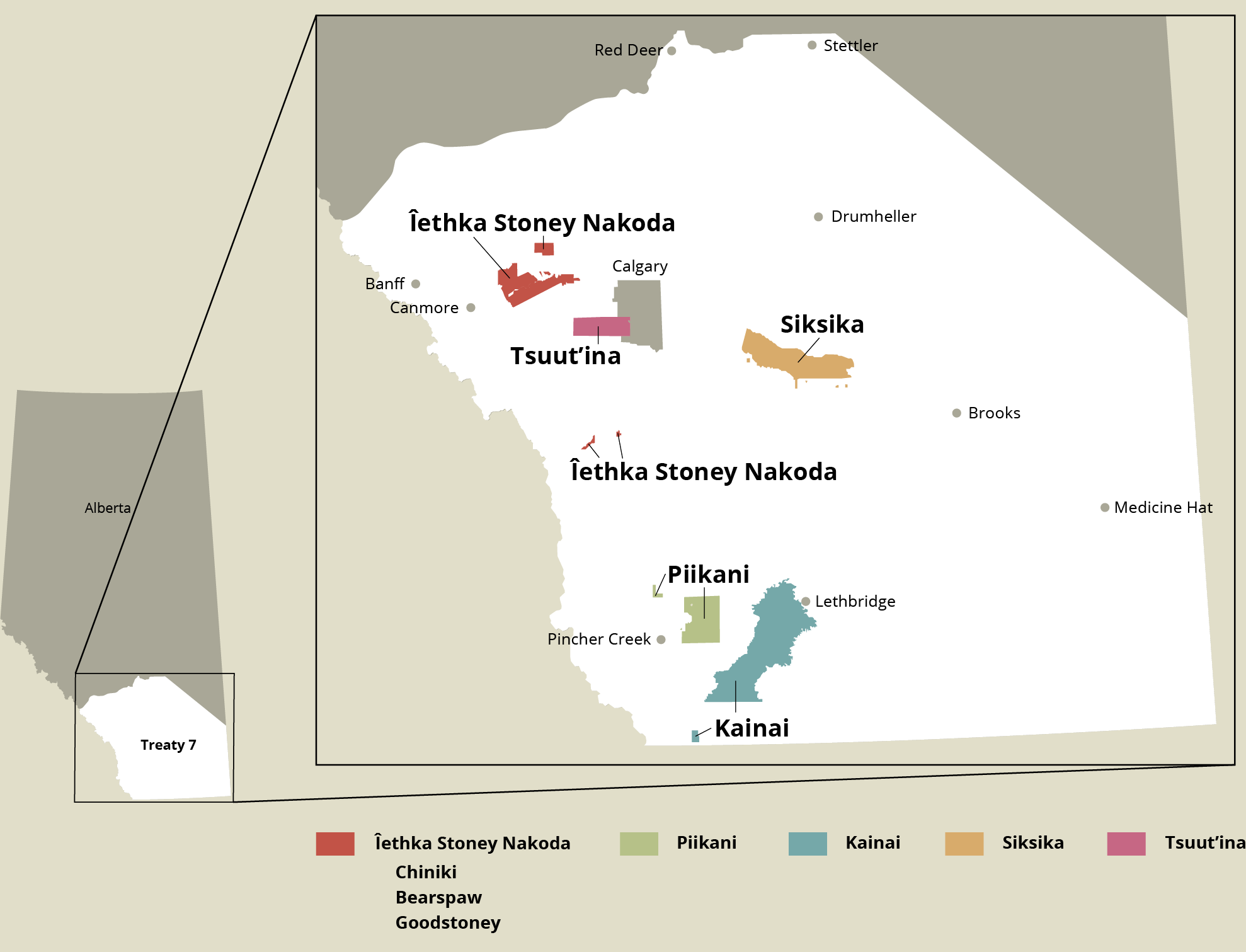

Current Treaty 7 reserves

Source: Modified from First Nations reserves and Metis settlements, April 2021 from Alberta Indigenous Relations under the Open Government Licence - Alberta

What is a land acknowledgement?

A land acknowledgement acknowledges the deep and interconnected relationships that First Nations have with all living beings, the spirit world, the universe and one another. It is a profound expression of respect and recognition for the original inhabitants of the land, and aims to make visible and rectify the historical injustices that have marginalized and silenced First Peoples.

Rooted in the principles of in-respect, in-relation and in-reciprocal pedagogy, Mount Royal’s land acknowledgement embodies the perspective of a treaty relationship. Briefly stated, it is about treaty-making that counters a long history of treaty-breaking. It is grounded in the standpoint that we are all treaty people, and aligns with the foundational concept of ethical space, as described in the 2023-2030 University Strategic Plan.

Land acknowledgements are typically spoken at the beginning of events or gatherings, and may also be included in print, digital or online publications and other materials. Formal land acknowledgements may be created to represent an organization or group, while individuals may choose to create their own personalized acknowledgements.

Why do we acknowledge land and territory?

“Reconciliation is about establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples in this country. In order for that to happen, there has to be awareness of the past, acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour.” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015, p. 6-7).

We acknowledge land and territory to articulate our commitment to fostering and enhancing the treaty relationship, by upholding and respecting the treaty agreements. In doing so, we challenge the historical actions that have separated Indigenous peoples from their land and strive to promote a future grounded in mutual respect and understanding.

Land acknowledgement protocols

- The land acknowledgement is given at the beginning of a gathering, typically as part of the welcome. It should be given as close as possible to the beginning of the meeting.

- An Indigenous person does not typically deliver a land acknowledgement if they are in their own territory.

- A guest of a gathering should not be asked to do a land acknowledgement. This should be done by the hosts of the gathering.

Speakers are encouraged to practice pronunciations prior to giving the acknowledgement. See the pronunciation guide.

Personalized land acknowledgements

Personalized land acknowledgements can be used for more informal gatherings such as classes, meetings, functions, presentations and any events or materials representing an individual or group.

A personalized acknowledgement is typically created by the person giving the acknowledgement and is based on their own perspectives and reflections. With that in mind, the acknowledgement should not be about or focus primarily on the speaker themselves; instead, it should concentrate on recognizing the land and the First Nations who have lived on the land since time immemorial.

When creating your own personalized land acknowledgement, you are encouraged to learn about the Indigenous Nations from the territory (sometimes referred to “as the ground beneath your feet”), the history of the land and any treaties, and the names (including pronunciations) of the Indigenous Nations and their communities. As you connect, visit with and understand the various Nations in a given region, you will be more familiar and comfortable with use and pronunciation.

Mount Royal’s institutional land acknowledgement may be used as a resource for the creation of your personalized land acknowledgement. For example, you may incorporate select components of the land acknowledgement into your acknowledgement, if you wish to do so.

Why should I personalize my land acknowledgement?

Personalizing an acknowledgement is a way to examine how colonization may have impacted your knowledge and relationships, or how influential Indigenous perspectives are on your life. This can be an act of decolonization; one way that you can demonstrate your understanding of treaty relationships and step forward as an ally.

In the creation of your own land acknowledgement, consider the following:

- Respectfully reference the First Nations who are indigenous to the land. Be specific and ensure current usage and pronunciation.

- Position yourself and describe your role in the treaty relationship.

- Focus on the land and Indigenous nations, not just yourself.

- Describe your commitment and the actions that you are taking or are willing to take.

Learn more about creating personalized land acknowledgements by exploring the resources below.

Resources

The following resources provide more information and details about Treaty 7 and the creation of land acknowledgements. This is not a complete list of resources available on these topics. It is intended to offer a range of information, ideas and perspectives.

Other Treaty 7 land acknowledgements

- Calgary Public Library – Our Land Acknowledgement

- The Calgary Foundation – Land Acknowledgement

- University of Calgary – Territorial Land Acknowledgement

- Southern Alberta Institute of Technology – Acknowledgement of Traditional Territories

- Bow Valley College – Acknowledgement of Land

- St. Mary’s University – Land Acknowledgement

Resources on creating your own land acknowledgement

- Centre for Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Land acknowledgements. University of Alberta. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://www.ualberta.ca/centre-for-teaching-and-learning/teaching-support/indigenization/land-acknowledgements.html

- Deer, K. (2021, October 21). What's wrong with land acknowledgments, and how to make them better. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/land-acknowledgments-what-s-wrong-with-them-1.6217931

- Huguenin, M. (2021, May 3). How to do a land acknowledgment. Trent University. https://www.trentu.ca/teaching/how-do-land-acknowledgment

- Kapitan, A. (2023, November 18). How to ensure that your land acknowledgment doesn’t perpetuate oppression. Radical Copyeditor. https://radicalcopyeditor.com/2023/11/18/land-acknowledgment/

- Native Governance Center. (n.d.). Indigenous land acknowledgment guide. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://nativegov.org/resources/a-guide-to-indigenous-land-acknowledgment/

- Native Governance Center. (2019, October 22). A guide to Indigenous land acknowledgment. https://nativegov.org/news/a-guide-to-indigenous-land-acknowledgment/

- RAVEN. (n.d.). Making a meaningful land acknowledgement and building relationship. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://raventrust.com/land-acknowledgement-guide/?gad_source=1

- Yellowhead Institute. (2019, October). Land back: A Yellowhead Institute Red Paper. https://redpaper.yellowheadinstitute.org/

Land acknowledgement resources

- âpihtawikosisân. (2016, September 23). Beyond territorial acknowledgements. https://apihtawikosisan.com/2016/09/beyond-territorial-acknowledgments/

- Asher, L., Curnow, J., & Davis, A. (2018). The limits of settlers’ territorial acknowledgments. Curriculum Inquiry, 48 (3), 316–334. https://doi.org./10.1080/03626784.2018.1468211

- First Nations Health Authority. (n.d.). Territory acknowledgements. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-Territory-Acknowledgements-Information-Booklet.pdf

- Lambert, M. C., Sobo, E., & Lambert, V. L. (2021, December 20). Rethinking land acknowledgments. Anthropology News. https://www.anthropology-news.org/articles/rethinking-land-acknowledgments

- Little Elk, W. (2022, November 3). Every time I hear a land acknowledgment . . . . Siċaŋġu Co. https://www.sicangu.co/news/land-acknowledgments (Original work published April 2021)

- Wilkes, R., Duong, A., Kesler, L., & Ramos, H. (2017). Canadian university acknowledgment of Indigenous lands, treaties, and peoples. Canadian Review of Sociology, 54 (1), 89–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12140

Treaty 7 resources

- Calgary Foundation. (2019). Treaty 7 Indigenous ally toolkit. https://calgaryfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/124715-Calgary-Foundation-Treaty-7-Indigenous-Ally-Toolkit-c.c.pdf

- Canadian Museum of History. (n.d.). Negotiating Treaty 7. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://www.historymuseum.ca/history-hall/negotiating-treaty-7/

- Canadian Register of Historic Places. (n.d.). Treaty No. 7 Signing Site National Historic Site of Canada. Canada’s Historic Places. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=15908

- Dempsey, H. A. (1972). Crowfoot, Chief of the Blackfeet. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Dempsey, H. A. (2010, September 15). Treaty research report - Treaty Seven (1877). Government of Canada. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100028789/1564413611480 (Original work published 1987)

- Glenbow Museum. (n.d.). Niitsitapiisini teacher toolkit. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://www.glenbow.org/blackfoot/teacher_toolkit/index.html

- Government of Canada. (2013, August 30). Copy of Treaty and Supplementary Treaty No. 7 between Her Majesty the Queen and the Blackfeet and other Indian tribes, at the Blackfoot Crossing of Bow River and Fort Macleod. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100028793/1581292336658 (Original work published 1877)

- Price, R. T. (Ed.). (1999). The spirit of the Alberta Indian treaties (3rd ed.). The University of Alberta Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780888647788

- Taylor, J. L. (1999). Two views on the meaning of Treaties Six and Seven. In R. T. Price (Ed.), The spirit of the Alberta Indian treaties (3rd ed., pp. 9–45). The University of Alberta Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780888647788-005

- Tesar, A. (2023, November 10). Treaty 7. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/treaty-7

- Treaty 7 Elders and Tribal Council (with Hildebrandt, W., First Rider, D., & Carter, S.). (1996). The true spirit and original intent of Treaty 7. McGill-Queen’s University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780773566378

- Treaty 7 First Nations Chiefs’ Association. (n.d.). [Treaty 7 First Nations Chiefs’ Association’s homepage]. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://www.treaty7.org/

General treaty resources

- Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Purich Publishing; University of British Columbia Press.

- Carter, S. (1999). Aboriginal people and colonizers of Western Canada to 1900. University of Toronto Press.

- Daschuk, J. W. (2013). Clearing the plains: Disease, politics of starvation, and the loss of Aboriginal life. University of Regina Press.

- Faculty of Native Studies. (n.d.). Indigenous Canada [Massive open online course]. University of Alberta. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://www.ualberta.ca/admissions-programs/online-courses/indigenous-canada/index.html

- Joseph, B. (2018). 21 things you may not know about the Indian Act: Helping Canadians make reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples a reality. Indigenous Relations Press.

- King, T. (2012). The inconvenient Indian: A curious account of Native people in North America . Anchor Canada.

- Krasowski, S. (2019). No surrender: The land remains Indigenous. University of Regina Press.

- Library and Archives Canada. (2016, November 2). Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Government of Canada. https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/aboriginal-heritage/royal-commission-aboriginal-peoples/Pages/final-report.aspx

- Library and Archives Canada. (2023, March 21). Treaties, surrenders and agreements . Government of Canada. https://library-archives.canada.ca/eng/collection/research-help/indigenous-heritage/Pages/treaties-surrenders-agreements.aspx

- Miller, J. R. (2018). Skyscrapers hide the heavens: A history of Native-newcomer relations in Canada (4 ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Mount Royal University Library. (n.d.). Indigenous studies | Primary sources. Mount Royal University. Retrieved July 22, 2024, from https://library.mtroyal.ca/indigenousstudies/indigprimarysources

- Poelzer, G., & Coates, K. S. (2015). From treaty peoples to treaty nation: A road map for all Canadians. University of British Columbia Press.

- Snow, J. (2005). These mountains are our sacred places: The story of the Stoney Indians. Fifth House.

- Vowel, C. (2016). Indigenous writes: A guide to First Nations, Métis, & Inuit issues in Canada. HighWater Press.

Further information

For more information about land acknowledgements, Indigenous protocols and honorariums at Mount Royal University, please contact:

Office of Indigenization and Decolonization

References

- Ermine, W. (2007). The Ethical Space of Engagement. Indigenous Law Journal, 6(11), 202. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/ilj/article/view/27669/20400)

- Government of Canada. (2024, June 26). (2024, June 26). About treaties. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100028574/1529354437231

- Podlasly, M., von der Porten, S., Kelly, D., & Lindley-Peart, M. (2020). Centering First Nations: Concepts of Wellbeing toward a GDP-Alternative Index in British Columbia. https://www.bcafn.ca/sites/default/files/docs/reports-presentations/BC%20AFN%20FINAL%20PRINT%202020-11-23.pdf

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (p.6). https://irsi.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/inline-files/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf