An intelligent choice: Learning to think in the age of LLMs

Since it was first visualized in the mid-20th century, the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) has rapidly accelerated and is now an integral part of modern life. However, as has been the case with any number of technological innovations, many are split on its implications.

Proponents see AI as a tool for progress, citing its potential to revolutionize health care, enhance productivity and help solve complex problems. Critics warn of significant risks, including job displacement, algorithmic bias, privacy invasion and even the threat of uncontrolled superintelligence.

Many see it as a tool, others a crutch and some warn that AI can be treacherous for those who use it blindly. The idea that machines could potentially learn to think on their own has been around since the late 1940s, when Alan Turing hypothetically mused about whether a human carrying on a text conversation with a computer and another person could tell the difference between the two. Back then, it was only a thought, but today, Large Language Model (LLM) tools such as ChatGPT, Microsoft Copilot and Google Gemini carry on realistic, human-like conversations, to the point where millions of people turn to them for advice, and answers to questions can be found in milliseconds.

LLMs are a type of AI, which creates systems that can perform tasks typically requiring human intelligence, such as problem-solving, comprehension and pattern recognition. LLMs fall under this definition and can understand and create human language through deep learning models. They then process massive amounts of text data, learning patterns and context.

Vendors constantly “retrain” their LLMs, and products incorporate user feedback, leading to their continuous improvement. That causes some to worry that LLMs will begin to make many careers, such as research and writing, obsolete. Joel Conley, an MRU Bachelor of Computer Information Systems graduate who now works as a web software developer, says AI is here to stay and people who want to remain professionally relevant need to learn how to best navigate a world with it.

“New, publicly available technologies have always been controversially received. Social media, the internet itself, television and radio all received similar pushback,” he says. “And while the criticisms and warnings often turned out to be valid, the benefits to society were overwhelming while turning out to have been less predictable than the drawbacks.”

Conley is optimistic that LLMs could be beneficial... if used correctly. It’s self-protective to proceed with some skepticism, Conley says, while stressing that information gleaned from an LLM, Wikipedia or the internet should always be double-checked.

Educators are in a unique position right now, as they are perfectly placed to assist in teaching ways to use LLMs that will be most advantageous. The problem is, however, that the tools are so good already that it’s tempting to keep falling into an ease-of-use trap.

MRU computer science professor Randy Connolly says he has noticed a trend towards fast internet searching for basic research. Assigning an actual paper book to read is “scary” for some students, and that, as he explains, is a problem.

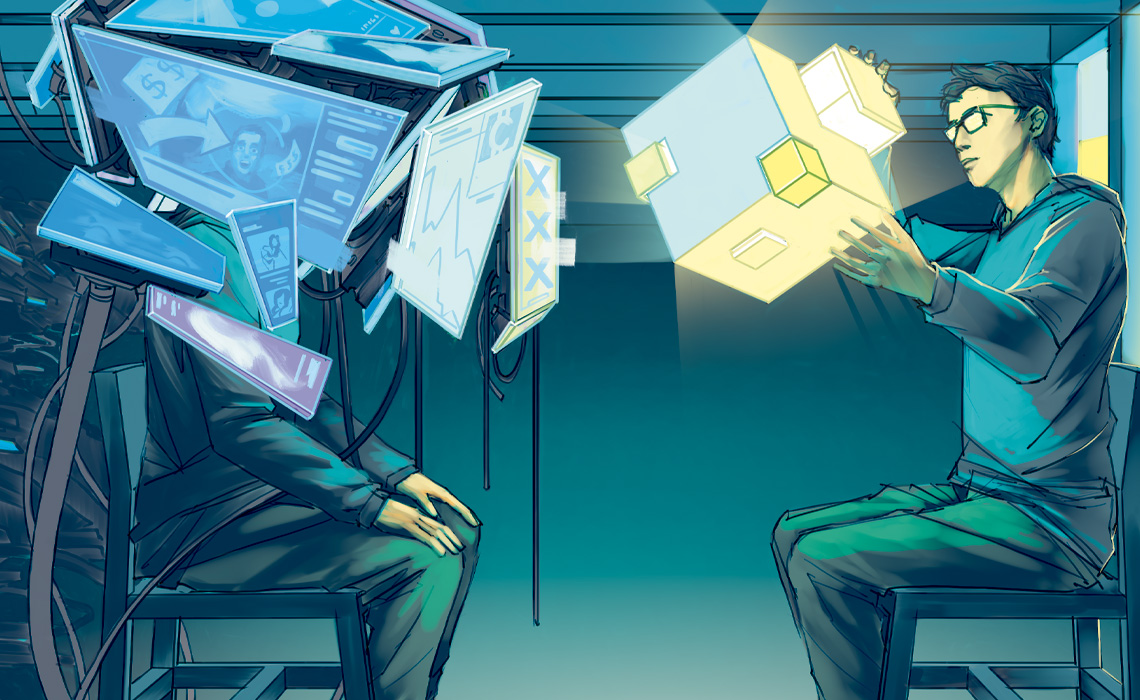

Enter the echo chamber

Human-crafted blogs and websites have predictably lost popularity to other channels such as vlogs and social-media platforms. Now, many sites such as Medium and Tumblr simply republish content created by people elsewhere instead. Automated agents take it from there, reproducing those republished efforts many times over.

“Google has become almost completely reliant on Reddit for actual novel human responses to human questions,” Connolly says. All of this creates an endless feedback loop where searches continuously “refind” the most popular search material, which often comes from the same sources or sponsored content.

“Over the past 20 years, one of the most replicable findings in user experience research is that users almost never go to the second page of the search engine results,” Connolly explains. “About 60 per cent will click the first entry, which is often a sponsored result, and 25 per cent will click the second entry.”

This generates Google’s parent company Alphabet a lot of revenue for directing traffic to the sponsoring website.

For context, Google represents 90 per cent of search traffic in Canada.

Connolly says the monetization of content comes with two costs. The first is obvious: sponsored information might not be reliable or accurate.

Conley agrees, saying, “The fact that some people blindly trust LLMs is a general skepticism-training problem. For the people who are overly trusting of this generated content, I’d be willing to bet their lack of skepticism is not limited to LLMs. It highlights a much broader problem that is, in my opinion, not unique or novel to this technology.”

The second challenge posed by the monetization of internet content is less obvious, but more alarming. Google may now be railroading users into an increasingly narrowed offering of ideas and information.

In an online environment “where almost everyone thinks alike because they are reliant on an information infrastructure that regurgitates a small subset of profitable (online ideas), valuable innovation and creativity struggle to find air,” Connolly says. “AI is exacerbating this problem.”

This environment promoting a curated set of ideas is counter to the traditional notion of the pursuit of knowledge and education.

“Higher education should be a time for young people to be exposed to unfamiliar, unconventional and demanding ways of thinking. University courses that asked students to engage with texts and ideas that were different from ‘normal’ were what made innovation and creativity possible.”

While LLMs can make research easier, there is something to be said for the classic angst of trying and failing, the effort necessary for the learning and creative processes.

“A key aspect of education has been struggle. The learning happens, in a sense, with the struggle, that’s the dialectic of knowledge. You feel constrained by your ignorance, by lack of capability, lack of experience and have to try to overcome that,” Connolly says. “That’s where learning happens. In that space.”

Learning is not passive, but an experience. And while a student might use LLMs as an assistant or a shortcut, Connolly cautions they (and others) risk short-changing themselves if they are overly reliant on them.

And there ought to be a lesson in that.

Kris Hans, a lecturer with the Bissett School of Business, was among the first at MRU to publish a transparent classroom policy on student use of AI writing tools. In Hans’ courses, students can use AI only under documented guardrails (disclosure, process evidence, fact-checking), with reflective work and strategic choices kept strictly human.

Students who use AI must follow Hans’ policy. For his Business Communication course, he says, “I use a math analogy: if the final answer is wrong, it is wrong. If they show their work and reasoning, they may earn partial credit. They must show their process, cite use, fact-check and revise into their own voice.”

Hans also teaches a course on Creativity in the Workplace, where “students start with their own ideas first, then can use AI for prompts, summaries or grammar. AI cannot write reflections or pick strategies.”

Most students are open to using LLMs and see value when they document their process and critique the output against course concepts, Hans says.

“When students copy and paste instructions without thinking critically, they are not applying the course concepts,” he cautions. “The result is weaker work and, often, lower grades.”

Adaptive learning a crucial skill

It is instructive to consider other advances that portended massive change. The introduction of the microwave brought high expectations it would transform cooking, with early ads touting it as capable of roasting a turkey — clearly not a thing.

“Ultimately, the microwave became just something for doing a very narrow range of cooking tasks, quick-and-easy meals, heating stuff already cooked. So, it has its niche and that’s it,” Connolly says.

But worry over the risks microwaves posed as people incorporated them into daily life was real. Some culinary schools briefly figured there was no point in teaching basic skills because people would just be microwaving meals.

Those skills, once lost, are hard to gain back.

Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan’s auto amputation theory speaks of how certain capabilities are lost when new technologies are adopted.

For example, once a phone number is stored in “Contacts”, there’s no reason to remember it.

“When we adopt a calculator, we lose the ability to do arithmetic. When we increase vehicle use, we lose our ability to walk places. It absolutely happens,” Connolly explains. “The question is, ‘What’s being amputated with this particular technology?’ Maybe I can live with a loss of ability to do arithmetic or remembering phone numbers. But what about education?”

Conley agrees that a lot of landmines in life and online can be avoided through being adaptive learners.

He says a tutor-at-your-fingertips can be valuable. And whether an LLM “results in brain-rot or brain-flex really depends on how it is used, whether the user’s prompts are ‘Can you do this for me?’ versus ‘Can you help me understand this?’

“Was something lost for the first generation that was taught math using calculators as opposed to doing everything by hand?” Conley asks. “Almost certainly — but I think you’d be hard-pressed to find modern people who think we need to reverse course on this, given the ubiquity and availability of calculators. In fact, how to use

more advanced calculators is itself a skill that is now taught so we should expect this to become the case for LLMs as they continue to evolve as well.”

Hans says, “I do worry some students may lose fluency if they stop writing and outsource thinking. The students also worry about skill erosion and authenticity alongside rising use, and privacy plus accuracy remain concerns.”

An afflicted internet

Connolly warns users must be diligent enough to make their way past the first page of search-engine results and work to find unique and expansive content.

In fact, the dead internet theory, which has been around for more than a decade, suggests that much of the activity and content on the internet, including social media, is being generated and automated by AI agents.

In reality, nobody really knows just how much content on the internet is artificially created, although there are estimates of up to 50 per cent and potentially higher on platforms such as X. It seems the internet isn’t quite dead, but could be dying.

“The idea of the internet was to have the world’s information at your fingertips. It allowed people access to information about anything,” Connolly says. “They could go far and wide and, of course, aspects of that are still true. Given attention tends to be narrow and short rather than deep, the internet as a research source is not so much dead, but it may be becoming a little bit comatose.”

It’s basically what “enshittification” alludes to, a term coined by Canadian tech and science-fiction writer Cory Doctorow. “It’s a fantastic little word meant to capture how software platforms degrade and essentially become more and more awful over time. The process of monetization around platforms leads to this,” Connolly says.

Connolly’s objective is to teach students to lessen reliance on internet-related research and revisit good, old-fashioned literature. That way they are not substituting, but supporting human thinking, creativity and curiosity.

Back to the basics

Universities need to arm students with the understanding of how to approach internet-related research, while at the same time preparing them for a world of work that is simultaneously embracing and apprehensive of AI at all levels.

“Sure, use Google Scholar to help you find relevant literature but then go and read actual journal articles and go read books,” Conley says. “Complement the internet with some traditional forms of knowledge.”

Overall, he is hopeful. Conley says, “I always remind myself that Socrates opposed the concept of the written word in favour of memory and oratory communication. But I think his concern was more rooted in the desire to preserve the world that he knew. I think it’s best that we cautiously consider a world that could be instead.”