Trickle-down effect

As Calgary spent the summer of 2024 under water use restrictions after a major water-main collapse interrupted the usually reliable flow from our taps, residents of the city at the confluence of the Bow and Elbow Rivers were confronted with a growing concern over our water supply, how it is delivered and what we use it for.

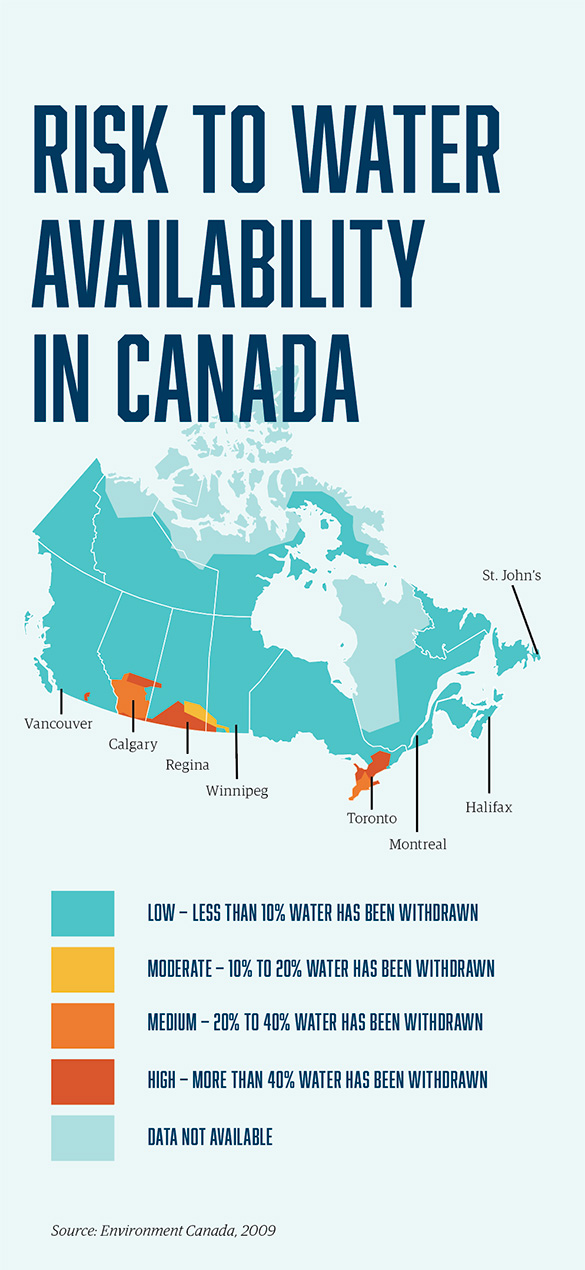

It is well known that Canada is rich in the world’s most precious resource, but Environment Canada says that while 20 per cent of the world’s freshwater resides within our borders, the reality is a lot more complex. Many assume there is almost a limitless supply of clean freshwater, however only about seven per cent of Canada’s supply is considered renewable, meaning it is replenished through precipitation and natural cycles. The rest is stored in lakes, underground aquifers and glaciers, and is classified as fossil water that is not easily replenished.

For Canada’s 40 million people — roughly 0.5 per cent of the world’s population — this still represents a significant water supply. However, more than half of our renewable freshwater drains north into the Arctic Ocean and Hudson Bay, making it largely inaccessible to the 85 per cent of Canadians who live in the southern regions. This geographical distribution means that while Canada’s water resources are abundant, they are unevenly distributed and often subject to high demand and environmental stress.

All of this highlights the need to conserve water. There is important work being done by MRU researchers and some of our amazing alumni as we continue to face infrastructure challenges and ongoing drought conditions. Simultaneously and contrarily, the floods of 2013 remain strong in our collective memories as municipal and provincial governments work to prevent future flood damage, and another set of MRU researchers look into the sociology of disasters and how people work together to overcome them.

An 'unlucky' break

Calgarians endured a long summer of short showers and varying degrees of water restrictions after the city’s Bearspaw South Feeder Main burst spectacularly at the beginning of June, sending thousands of litres of water flooding out onto 16 Avenue N.W., leaving the communities of Bowness, Montgomery and Point McKay with empty taps, prompting a state of local emergency as the city’s potable water resources were placed at risk.

The Bearspaw South Feeder Main delivers about 60 per cent of the city’s treated water from the Bearspaw Water Treatment Plant.

A planned inspection of the water main had started in the spring and was planned to be complete by fall 2024, but it unfortunately broke before work was finished, explains Dr. Jay Huang, PhD, an assistant professor with MRU’s Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences.

“In my opinion, this water main break was an unexpected scenario, but the protections are there and the city is trying its best to maintain their pipe conditions,” says Huang, who conducts research in the field of water resources and hydrology focusing on statistical hydrology, hydrologic cycle under urbanization and climate change, regional/local hydrologic analysis and hydrologic/hydraulic modelling.

It is not the first time that Calgary has grappled with a major water challenge.

In 2004, a water main along McKnight Boulevard broke, flooding streets and disrupting water service to more than 100,000 people. Degradation of the pipeline’s coating and weakening steel wires that fortify the system were partially to blame.

Huang says that incident prompted the City to introduce a year-round, proactive inspection program to identify leaks before they become catastrophic.

And it worked until that unlucky break last June. Unlike many other Canadian cities, Huang says, Calgary has a robust program to inspect, maintain and repair its aging pipes. In part, it relies on robotic devices to search for leaks via ultrasound, which provides an acoustic signal increasing in crescendo as it approaches an area of concern.

Huang says the system to thwart failures is thorough and impressive, albeit not infallible.

“We have to accept the truth — that there are many pipes buried in the ground that are more than 50 or 60 years old,” he says.

What goes unseen

Under Calgary’s surface lies a complex water infrastructure system. The water lines bring the precious resource to homes and businesses, sanitary lines collect and deliver toilet and kitchen water to waste treatment plants and storm lines collect rainwater.

The water lines sit on top of the sanitary and storm lines and are buried at least 1.2 metres below ground. They serve a purpose pretty much unnoticed by many. Of course, that dramatically changed last June when the streets of Bowness became a rushing river. The Bearspaw South Feeder Main break cracked open pipes and Calgarians’ eyes to a system that provides everything from showers to drinking water to more than 1.5 million people.

The ongoing inconvenience of water restrictions and a relentless push by city officials to cut back on use on the homefront highlighted our constant reliance on that system.

And when city-wide restrictions were lifted, ending the crisis that stretched over much of the summer, few remained unaware of the system that delivers water on demand.

Water travels from water treatment plants all the way to taps. The Bearspaw Water Treatment Plant, for instance, sends water as far as Airdrie and Chestermere.

The rapid pace of developments in the city adds more demand to original infrastructure, which is why the city is trying to add more pipes to the system.

It’s a lot of energy, and it’s a lot of pressure.

Encouraging conservation as de rigueur

The more water used, the more pressure on the system, which begs for an ongoing need for conservation. Huang explains more conservative water use means less wear-and-tear on the pipes, adding longevity to an already aged system.

“Water is so precious,” he says. “There is a lot of cost associated with construction, operation and maintenance and a lot of money is invested into water distribution and water treatment.”

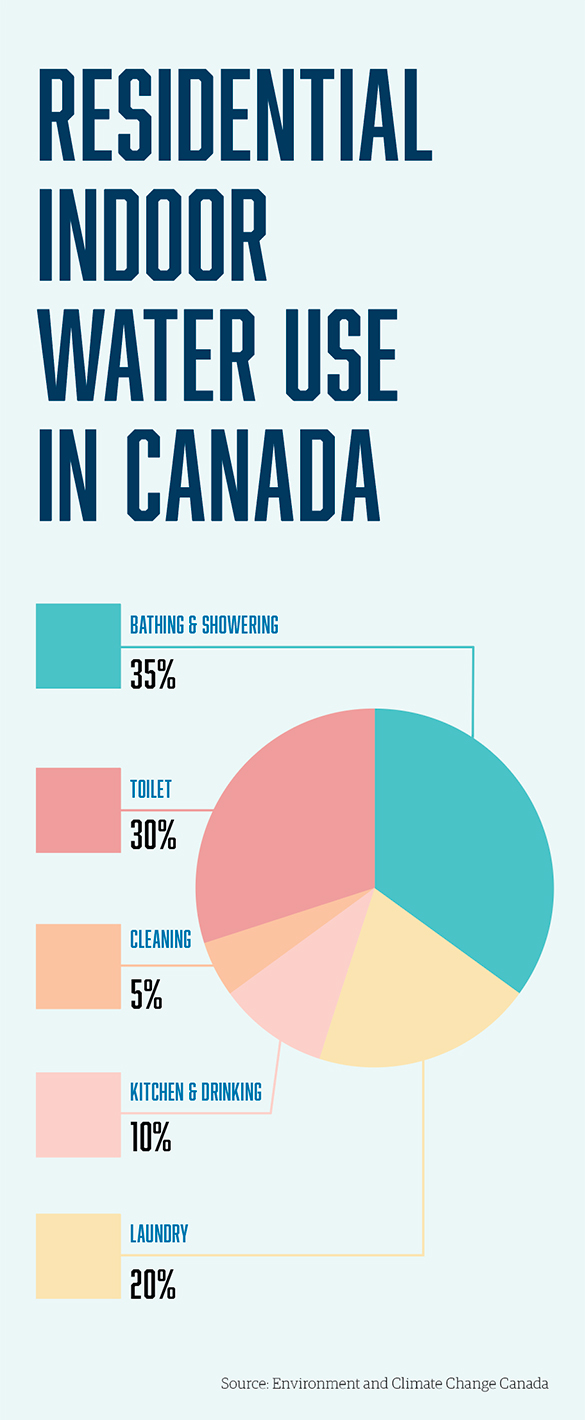

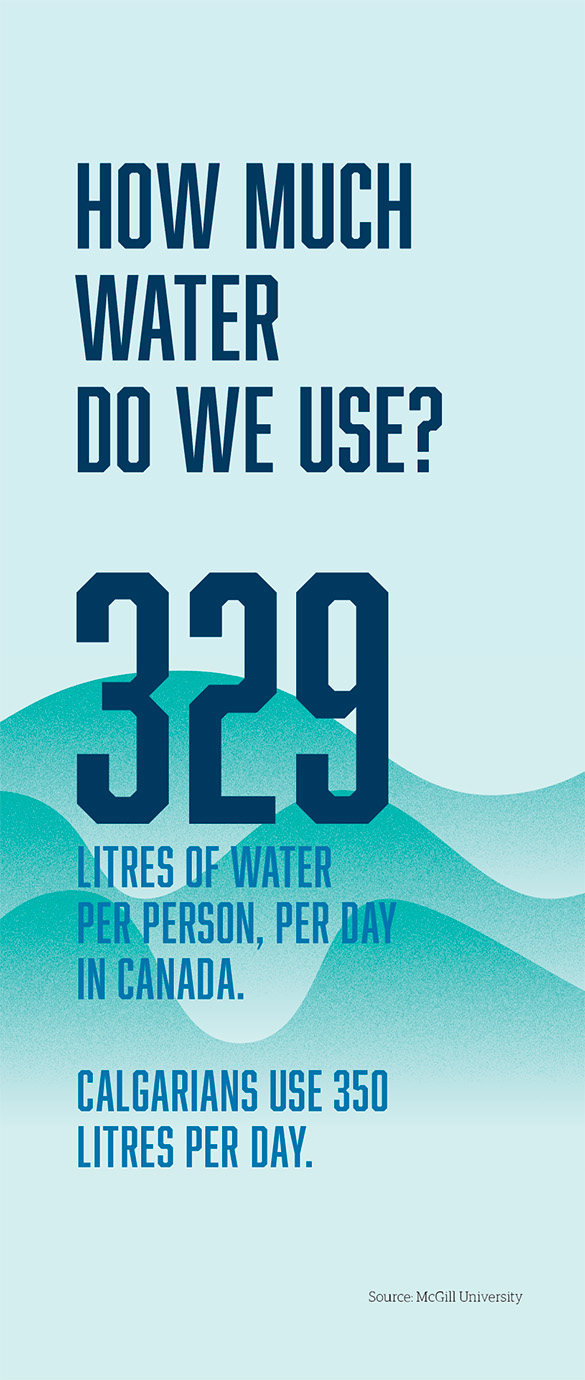

You might not think that is top of mind for many when looking at daily demand.

“Our daily water use in Calgary is about 350 litres per day, per person. That’s a lot compared to other places in the world,” Huang says. “We are rich in water resources and have a lot of water available to use, but we need to take a step back a little bit and we should be aligned with the daily average use (globally), which is about 150 litres.”

The University of Toronto’s Infrastructure Institute estimates about 30 per cent of the water infrastructure nationwide is in fair, poor or very poor condition, and director Matti Siemiatycki, PhD, says not investing in maintenance leaves municipalities “ripe” for catastrophic, costly failures.

Huang says in Calgary investments are being made to bolster the system.

The North Calgary Water Servicing Project, currently in the design phase, involves the construction of a new 22-kilometre long water feeder main and multiple support facilities that will deliver 100 million litres of water per day to support current and future population growth in the northwest area of the city. Construction is scheduled to begin this year, with a projected completion date of late 2029. The new line will run north from the Bearspaw Water Treatment Plant near Stoney Trail and Nose Hill Drive, then cross under Crowchild Trail and continue up to 144 Avenue N.W., then connect to the Northridge Feeder Main at 144 Avenue and 14 Street N.W.

In February, City of Calgary officials announced they are exploring a micro-tunnelling approach that would minimize the disruptions and service outages to water use. A second pipe would parallel the Bearspaw South Feeder Main to ensure redundancy and enable necessary repairs on the existing feeder main without interruptions in service.

“Taking a look at water-main break disasters, compared to other cities, we are still doing a decent job and still investing and trying to install new water feeder mains to serve the increasing population in Calgary,” Huang says.

Every drop counts

Dr. Mathew Swallow, PhD, an associate professor in MRU’s Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, remembers his grandfather recounting the time night hijacked day.

“He was telling me about the dust bowl in the ’30s and how daytime turned into night in Saskatchewan,” Swallow says. “All of a sudden, a storm would go through and it would be pretty much pitch-black out.”

The dust bowl era, which blew away 75 per cent of the topsoil in some areas, created severe economic upheaval and hardship over the Great Plains of North America, leaving many desperately trying to protect exposed soil from being stripped from the landscape. It is estimated that conventional farming practices have caused nearly half of the world’s most productive soil to disappear over the last 150 years, threatening crop yields and contributing to nutrient pollution, dead zones and erosion.

These days, many who work the land are just as reliant on Mother Nature, who can give as easily as she takes. Amid ongoing drought conditions in Alberta, there’s an urgent focus on keeping water in the soil. In Calgary, perhaps, more than ever.

“I’m happy people are becoming more water conscious about soil,” Swallow says. “It’s too bad it took a water main break for it to happen. It would be nice if people changed their practices to be a little more water smart.”

MRU alumna, geologist and farmer Tricia Fehr (General Studies Arts and Sciences Certificate, 2003) is already hyper-conscious of safeguarding the water supply on her family’s mixed-use farm near Crossfield, AB, against daily threats to their livelihood. The summer of 2024 marked the first drought she has been involved in while farming as her main career.

Fehr explains how less moisture meant harvesting her wheat early, pulling in a slightly below-average crop.

“Dad talks a lot about what it was like in the ’80s. I remember going with him to pump water out to the cows,” the fifth-generation farmer says.

When a pasture creek on their land stopped flowing and began drying up, she hauled water to cows, careful not to put too much pressure on the aquifer she shares with her parents, who farm nearby.

Old and new solutions

At Fehr’s farm, they collect rainwater as it runs off the barns and house in several 1,000-litre tanks. Fehr’s husband also stopped cutting the legumes growing around the bottom of the trees so they can grow tall in the fall to trap snow over the winter.

“The more snow we can get the better,” she says. “It starts everything off right in the spring.”

With no irrigation in her area for crops, water is a constant worry. To alleviate some of the stress, many farmers like Fehr have become very creative.

On Fehr’s farm, they don’t till the soil other than when they seed it. After straw comes out of the combine, it’s chopped up and sprayed out as a blanket, which then slowly disintegrates to add nutrients and provide a protective armour for the soil.

“We’ve mulched every tree on our property so we don’t have to water,” she says.

“Last year, I’m sure neighbours thought I was crazy. In the hay field I put up huge snow fences to trap more snow because the year before it was really dry,” she says. “I think you just adapt, that’s part of being a farmer, go with the flow. You wouldn’t last very long as a farmer if not. It’s all out of your control.”

They are just as diligent on the homefront.

Water taken from their aquifer is pumped over to their house, then to septic tanks as grey water and sewage. Solids go to one side while liquids go to a second tank, which is eventually pumped out into grassy areas.

“We think about it all the time,” Fehr says. In April, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada noted conditions for 2025 are mainly in the normal range, however the months of May through July are pivotal.

Where plant life begins

For MRU soil expert Swallow, it all comes down to protecting soil, which stores water by acting as a sponge. Tiny air spaces between the soil granules allow it to hold moisture.

For his research, Swallow has several small sites on farmers’ fields where he has placed rocks to create protection and stop moisture from evaporating. Farmers on Easter Island, well off the coast of Chile in the south Pacific, rely on this lithic mulching approach to help regulate temperatures and release mineral nutrients as the stones weather. Swallow is comparing the effectiveness of stone mulch to straw mulch and bare soil, researching whether it can be an effective water-conservation tool in Canada.

Less academic albeit real-life research last summer saw many Calgarians bewildered that some plants did not suffer without their usual daily watering during the water restrictions. Many lawns refused to yellow and hardy petunias persisted.

Swallow isn’t surprised.

“The rule of thumb is that gardens require about an inch of water a week. If you are watering every day, you are probably watering more than what the plant needs,” he says. “When we have lots of water, we usually don’t think it’s a big deal. When, in fact, water conservation is always a big deal.”

He suggests boosting water available to plants by adding organic matter like compost, which holds two to three times its weight in water.

Underscoring it all is the need to protect the topsoil. In Alberta’s grassland system, topsoil replenishes itself to the equivalent of the thinness of a sheet of paper per year. In the U.S. alone, soil on cropland is eroding 10 times faster than it can be replenished.

“And that can disappear in one rain or wind storm,” Swallow says. “You want to keep the moisture in the ground. You have to protect it.”

Research shows disasters do not divide

Severe events provide the necessary training tools to prepare for the next inevitable disaster. Dr. Caroline McDonald-Harker, PhD, director of MRU’s Centre for Community Disaster Research (CCDR), began research in the field after the 2013 southern Alberta floods.

“Canada had not experienced, up until that point, a significant number of disasters,” says the associate professor of sociology. “It was still quite new from the Canadian context.”

The CCDR was created to fill that need for evidence-based research from which organizations can understand, prepare for, recover from and develop policy around disasters.

“I don’t think any of us thought, 12 years ago, there would be this many disasters,” she says.

As anyone living in Alberta knows, they just keep happening.

Alberta is a hotbed on the Canadian landscape and is home to five of the top 10 most costly natural disasters in the country’s history.

In 2016, wildfire ripped through Fort McMurray, forcing nearly 90,000 to flee the community. Of course, the smaller mountain community of Jasper was hit with similar circumstances in July 2024, leading to $1.1 billion in insured losses. The next month, Calgary was hit by a huge hailstorm, racking up a massive $3-billion insurance bill.

An underlying theme?

“We’ve seen that time and time again with disasters people do come together in moments of crisis,“ McDonald-Harker says. “I personally think, despite living in a very hedonistic world that focuses on individuals, people deep down are good.”

That is backed by research.

MRU disaster expert Dr. Timothy Haney, PhD, says disaster research dates back to the ’50s when the U.S. government wanted to predict what survivors might do if the Soviets dropped a nuke on the States.

“They figured it probably was not very ethical to drop a test nuke,” the professor says.

Instead, scientists relied on research gleaned after hurricanes and tornadoes to debunk “the perception disasters fuel the worst in us — shooting, rioting and every person for themselves,” with the enduring finding “that panic and disorder typically doesn’t happen.”

Real life illustrates that rather than rampant greed, resource-hoarding and violence unfolding — disasters unite people.

“The flood, Jasper, COVID, people do things for one another,” he says. “The optimist in me thinks that it is human nature, that we care about one another. The social scientist thinks it’s about reciprocity. We take care of our neighbours because we think we may need them one day.”

Haney benefitted from that kind of prosocial behaviour first hand after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, where he was studying at the time. He saw the best of people at the worst of times. Although it was two decades ago, living through it still affects him.

“I find myself far less attached to things or possessions,” he says.

It likely left anxiety, as disasters do, but it also taught him to be better prepared.

McDonald-Harker says a by-product of disasters is often a change in behaviours to lower impact on the environment we all share.

After the 2013 floods, for instance, her research found some families “became more aware of their susceptibility to disasters and the need to consider and mitigate such risks by focusing more on the environment.”

Other, well-intentioned parents assured their children the flood was an extremely rare event that was unlikely to repeat in their lifetime. It could be comforting in the short term, perhaps, but didn’t allow them to prepare for the eventuality of another disaster unfolding.

“Guess what just happened three years later? The Fort McMurray wildfire happened,” she says.

From the ashes ...

In many cases, McDonald-Harker says resilience is often a post-disaster take-away.

“Resilience is elastic, like a muscle that can be strengthened. It’s not either you have it or you don’t. It can be learned and something individuals can practice,” she says. “The more we go through disasters the more we can learn and can be better prepared. It’s not all doom and gloom.

Lots of research shows the opportunity to grow from very difficult circumstances.”

The openness employed by city officials during the water crisis forged trust with Calgarians who, for the most part, relied on them for the facts.

Its messaging, along with restrictions and encouraging Calgarians to reduce their water usage as “a contribution to the collective good,” promoted greater uptake, she adds.

Because disasters increase risk perception for some, Haney says it is directly related to some taking steps to mitigate potential perils.

Sadly, it can also heighten anxiety.

“In Calgary, after the flood, people told us they were going to bed fully dressed with shoes on because if they wake up in the middle of night they want to be ready to run. Like so many things in life, it’s a double-edged sword,” he says.

Far from being inevitable and immune to human efforts, Haney says disasters do not happen randomly.

“For centuries, people have said they are acts of God, but the reality is that there are many human decisions that place people at risk. It’s a human decision to build houses in a floodplain and to build communities at the wildland-urban interface, which puts them at risk for wildfires,” he says.

He says substantial research shows climate change is the new global reality, with Alberta predicted to warm by four degrees Celsius by 2050, double the world’s rate.

A collective decision to emit carbon into the atmosphere will continue to have consequences and set humans up for an uncertain future, he says.

“The more warming, the more extreme events we get. Some of our big risks here are drought, wildfire and water scarcity. And climate change makes pandemics more likely to occur in the first place,” he says.