Discovering the global context of the 'cowboy'

The history of ropers and riders is much more diverse that we think

— Mount Royal University | Posted: July 7, 2023

Roy Rogers, king of the cowboys.

Author’s note: The term “cowboy” in this piece refers to ranchers, herders and horse riders of all genders.

Every summer, cowboy culture gets a short, yet intense, period of interest in Calgary as the famous Stampede transforms the city — and the attire of many of its citizens and visitors.

The iconography that many North Americans typically associate with the “cowboy” has largely been built through Hollywood and television productions, both old and new. From classic heroes like John Wayne (The Duke) and the Lone Ranger to the Dutton family patriarch on Paramount's Yellowstone (played by western movie fixture and 2022 Calgary Stampede Parade Marshal Kevin Costner), the cowboy’s familiar hat, boots and maverick attitude are a mainstay in North American storytelling.

The real history of the “cowboy”, however, is much more diverse and widespread than what classic films and HBO television shows might portray. Traditions, events and cultural practices based around horses find their beginnings far from North America, thousands of years in the past.

Cowboy lifestyle has surprising origins

Dr. Carolyn Willekes, PhD, is a classicist and professor in MRU’s Department of General Education. An equestrian herself, her research and lecture topics include the history of the horse. “The traditions are relatively gender-inclusive and multicultural if you go back far enough in time,” she says.

One of the biggest surprises for many people, Willekes says, is where, and how far back, horse-related traditions begin. The cowboy, as she explains, is not a North American invention that started in the “Wild West” years of the colonization of the United States.

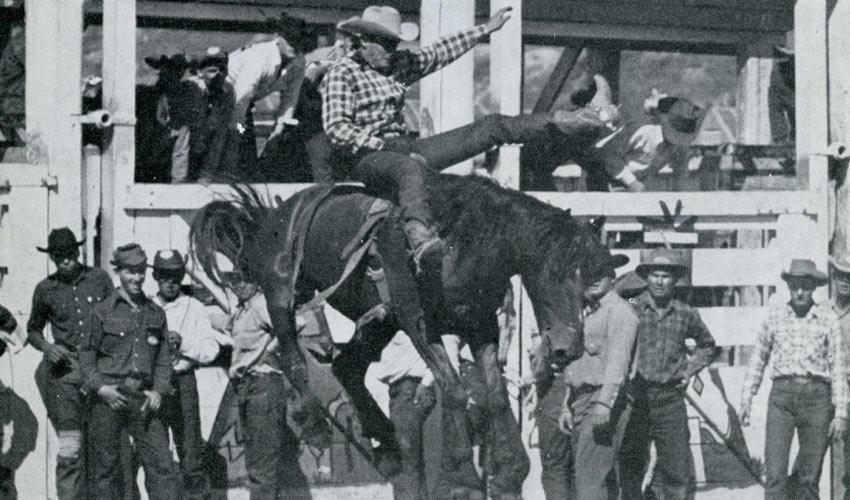

Bareback competitors struggle to stay mounted on a wild bronco for a least eight seconds with only a narrow leather belt around the horse’s body to hold onto. The belt can only be held with one hand and the other must remain in the air. Riders must spur their horse out of the gate and keep their legs in motion, extending their feet forward and then pulling back in a spurring motion for the duration of the ride. Successful riders have a strong wrist and back, good balance and are generally lighter than saddled bronc competitors.

“If we define a cowboy as someone who rides horses and herds animals, we can use archaeological and visual records to trace the symbols and tools we use to identify someone as a ‘cowboy’ back to the domestication of the horse, which was around 5,000 years ago on the steppes of central Asia in the area that’s now Kazakhstan,” she explains.

Nomadic groups originally began the taming process for horses as a food and milk source. They rode bareback, wore boots and managed other animals as they moved across the grasslands.

Willekes clarifies that, while it is challenging to pinpoint exactly where and when the horse was domesticated, the event was certainly a turning point in how people managed their lives, economies and livelihoods. “At the most basic level, that’s the birth of the cowboy — these nomadic groups in Central Asia who are migrating across the steppe and using horses to manage their animal resources. That usually surprises people,” she says.

As using horses for herd management became more commonplace, the spread of the domesticated horse began. Introduced to communities throughout the world by trade, travel and conquest, local traditions begin to form around horses.

Ranching traditions thrive and spread through ancient Europe to the Americas

While ancient Greece is known as the birthplace of some of the modern concepts of philosophy, politics, art and literacy that we know today, it is also one of the original homes of rodeo-type events. Thessaly, an ancient and modern region of Greece, was famous for its horses and cattle. Combining the two into a “rodeo” sport, bull wrestling was born. Likely part of a festival honouring the god Poseidon, various depictions of bull wrestling can be found on coins from the city-state of Larissa from the years 450 to 320 BCE. These coins suggest that the rider leapt from his horse and wrestled the bull to the ground by grasping its horns, much as in the modern rodeo sport of steer wrestling.

Even some of the clothing worn wouldn’t be out of place at a modern rodeo festival. “When you look at vase paintings from that era, the ancient Greeks had giant, wide-brimmed hats for travelling on horseback that they would have worn to keep the sun off. It looks like a sombrero,” Willekes describes.

The culture began moving across Europe, with evidence of “cowboys” in what is now modern Tuscany (formerly Etruria) in Italy. “You constantly see horses and bulls in Etruscan art, who were known for their equestrian skills,” Willekes says. Migrating into the medieval world, strong traditions of ranching, riding and cattle management emerged in Tuscany, with “cowboys” called the Butteri. To this day, the Butteri raise impressive, long-horned Italian cattle. “They have their own versions of rodeos that are more medieval or martial-combat in style, but the whole idea is a festival that celebrates their way of life.”

A map displaying horse migration across the world.

Moving across Europe through the Middle Ages, cowboys called “The Guardians” herded cattle on the marshes of the Camargue region of France while the cattle and horse husbandry traditions of southern Spain migrated into the Americas following contact and settlement by the Spanish. The pampas of Argentina and the sprawling grasslands of Mexico were ideal for large groups of cattle. After European settlers claimed the land and set up their haciendas, they began importing and breeding cattle and horses.

“The people indigenous to the land were trained to become riders, basically to become cowboys, or vaquero, and that’s where we see the idea of rodeo develop,” Willekes says. “They have a rich rodeo tradition in Mexico (Charrería), and that comes from Mexico up into Texas. The knowledge of rodeo’ing and of cowboy’ing actually begins in Mexico and Central America and then makes its way up north.”

Modern times show racial and cultural diversity

The more familiar image of the modern cowboy — usually a white man in boots with spurs, wearing a wide-brimmed hat and large belt buckle and seated atop a horse — begins to take place during the colonization of the Americas.

However, Willekes notes, it is important to acknowledge that ranching traditions, particularly in the southern United States, had a reality that was much more diverse. “If we look back to the 1800s when ranches are emerging in Texas and western North America, at least a quarter of all cowboys were Black. But if you look at the history of the cowboy, it’s presented as white. So that’s very much been erased.”

Particularly during the American Civil War, many white ranchers relied on enslaved people to manage their cattle and horses while they were away fighting. By the time the war ended, and enslaved people were emancipated, they had gained considerable ranching skills and expertise; many were hired by ranchers to continue the work once the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863.

“In the iconic cattle drives going through Texas and the south bringing cattle up to the northern parts of the United States, a large portion of the people who would have been involved in that weren’t white. They were Black. They were skilled cowboys. In the south, people were kind of aware of this. In the northern U.S. and up into Canada, it was not largely well known,” Willekes explains.

John Ware, rancher, ca. 1902-1903. Source: Glenbow Archives, NA-101-37. Used with permission.

Awareness of the skills of Black cowboys began to grow following an all African-American rodeo in New York’s Harlem neighbourhood in 1971. The community in Harlem was surprised to learn there were Black cowboys — all they had ever seen was the Hollywood version. The realization that there was this rich culture around the African-American cowboy all of a sudden started to come to the forefront.

“In fact,” Willekes says, “the Lone Ranger — one of the most iconic figures in Hollywood lore — who in Hollywood renditions is always white, is probably based on a Black man named Bass Reeves, who was one of the first Black sheriffs and became very famous for doing a lot of the things that we see the Lone Ranger doing. His story was fascinating to writers, movie creators, comic book creators and others. But they made a very deliberate decision to make the Lone Ranger white, when in reality the inspiration for the Lone Ranger was Black.”

People of colour and Indigenous people are connected to and played very important roles in this tradition. But, there have been deliberate decisions made to whitewash it to suit a target audience and to further marginalize particular groups, Willekes says.

“Now, there are some really interesting studies, movies, documentaries, coming out that are looking at the richer tradition. Cowboys are not a North American invention — they’re not from Texas or Alberta. Yes, we have cowboys here, but we didn’t invent them and they aren’t exclusively white.”

Closer to home, here in Alberta, John Ware — the famous Black Canadian cowboy — was an integral part of the beginnings of southern Alberta’s ranching industry. An excellent horseman, he was among the first ranchers in Alberta, arriving in 1882 on a cattle drive from the United States and settling to ranch until his death in 1905.

Indigenous communities across the plains were quick to integrate horses into their ways of life. “Research is showing that the horse moved across North America far quicker than we’d previously thought,” Willekes says. “It seems to suggest that Indigenous communities embraced the horse and very quickly figured out how to ride, manage and use them to great success.”

Within a generation, the horse became an important part of warfare, sports, identity, status and hierarchy, artistic expression, cultural expression and livelihood.

“What we’ve seen more recently at Stampede is the ‘Indigenous Relay’ — and I don’t know how they do it! They are such impressive riders because they ride the horses bareback and have to spring onto them from the ground. The fact that they are racing around that track without saddles or stirrups shows their skill and how deeply woven the horse is into the fabric of their society and identity.”

Cowgirls break barriers

Prior to the First World War, it would not be a surprise to see women fully participating in ranching and rodeo in North America. On the ranches, women were herding, roping and helping with other various aspects of herd management; in the rodeos, they were riding broncos and competing against their male counterparts.

Miss Flores LaDue (born Grace Maud Bensell) was a popular trick roper and Wild West Show performer. In 1906 she married Guy Weadick, a trick roper and showman, who is credited with the initial idea of a "Frontier Days and Cowboy Championship Contest" in Calgary. Weadick and LaDue were instrumental in planning the first Calgary Stampede in 1912. LaDue became the first World Trick Roping Champion and held the title for two years before retiring undefeated. She was known for popularizing the Texas Skip, a trick where the lasso is spun vertically and the performer jumps through the spinning loop.

“It wasn’t a gender-segregated job. That’s something that started to happen in post-war pop culture,” Willekes explains.

“It’s in the post-war period, with the professionalization of rodeo and the creation of rodeo associations run exclusively by men, that women were pushed out of the narrative. Women had to create their own rodeo associations, which are, of course, marginalized compared to the others.”

The social changes started to reflect in rhetoric, popular culture and representations of rodeo and ranching culture, thereby reinforcing the new norms. It wasn’t until 1948, with the creation of the first-ever professional sports association created solely for women by women, the Girls Rodeo Association (now the Womens’ Professional Rodeo Association), that women were able to push for gender parity by successfully advocating for women’s inclusion in the professional rodeo circuit and for better pay through the 20th century and to this day. Now, the association is multinational and women feature prominently in professional rodeo events.

"Horse people everywhere"

The history of the horse in the western world and the cowboy identity are multi-layered. The cowboy identity finds a solid home in many parts of Alberta, particularly during the Calgary Stampede, which has also grown and changed over the years to incorporate all of those who are skilled and interested in horsemanship.

“Wherever horses show up — and it’s an introduced species to most parts of the world — people find this relationship with it and incorporate it into their own cultural traditions. Interesting, because it’s primarily an animal of conquest. It got to most parts of the world through conquest and colonialism, yet people realize that it’s useful and a significant status symbol, and build social structures and practices around it.

“You find horses everywhere in the world, from Siberia to Patagonia. And you can find horse people everywhere!”