MRU neuroscientist speaks of lived experience with bipolar disorder

Dr. Adrienne Benediktsson, PhD, is a neuroscientist who recently put out a podcast detailing her first major episode.

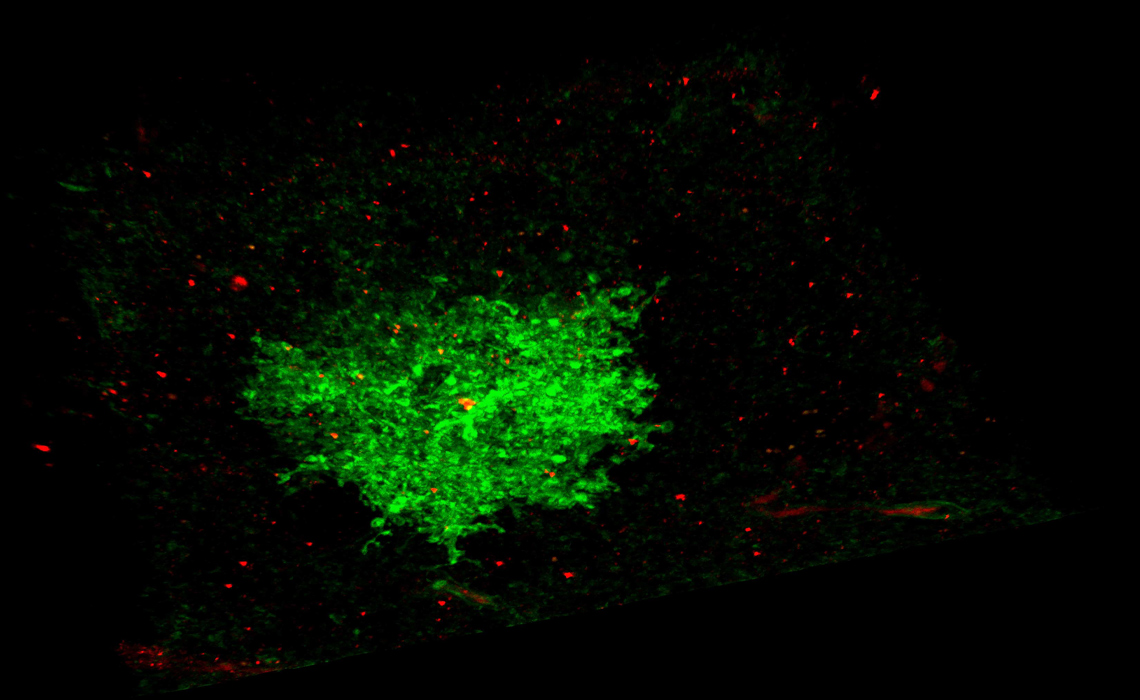

Mount Royal associate professor of biology Adrienne Benediktsson, PhD, fell in love with the brain — in particular, the astrocyte — while an undergraduate student at Iowa State University. A true morphologist, “someone who loves looking down microscopes,” Benediktsson was struck by the incredible intricacies of the glial cells, saying, “Astrocytes are simply beautiful under the microscope.”

The first astrocyte she saw was that of a Brazilian opossum while a graduate student. This led to research “primarily focused on the structure of astrocytes, including looking at how tiny microdomains, similar to neuronal synapses, were distributed within astrocytes’ cellular structure.”

Benediktsson explains that astrocytes are a type of brain cell that were ignored and thought to be unimportant for many years.

“The only purpose of astrocytes was thought to be a housekeeping cell making sure that neurons were well-cared for. Research over the last few decades has shown that astrocytes directly affect how neurons communicate. They are now thought to be much more active participants in cognition, particularly in more complex organisms, no longer just supportive cells but integral parts of how brains function,” she says.

Microdomains are most commonly related to neurons, where “small structures, known as synapses allow neurons to communicate from neuron to neuron. The more synapses there are, the more complex the neuronal communication.”

However, Benediktsson says that microdomains do not end with neurons.

“That description of microdomains within the nervous system ending with neurons doesn't tell the whole story, especially in the human brain. Astrocyte branches surround synapses and can affect how neuronal synapses talk to one another. It’s also true that the more complex the organism the more complex the astrocytes.”

Communication at synapses is far more dynamic with complex astrocytes and leads to more interesting neuronal communication and cognition (learning and understanding), Benediktsson says.

“Apparently, Einstein's neurons were pretty typical, but his astrocytes had a lot more branches and more intricate structure.”

The astrocyte has played a major part in Benediktsson’s research. In this photo the astrocyte appears green and the synaptic proteins appear red.

This interest in the brain and cognition is especially poignant considering an event that would occur during Benediktsson’s graduate studies. She would experience a terrifying manic episode following a conference focused entirely on astrocyte research, where she was thrilled to talk about her passion with some of the finest minds in the world. It was during the trip home that she began displaying extreme changes to her behaviour, acting entirely not like herself in mid-air.

The result would be a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Benediktsson bravely shares the entire encounter on a talkBD Bipolar Disorder Podcast titled “I Survived Mania at 30,000ft.”

Unfortunately, when COVID hit Benediktsson lost access to the mouse brains used for her astrocyte research, so she pivoted.

“I now do a type of research called autoethnography that looks at my lived-experience with bipolar disorder and the neuroscience behind it. As part of that research I produce pieces, in this case through CRESTBD, that speak to both.”

Watch “I Survived Mania at 30,000ft” on TalkBD.

Why is it important to you to speak about your bipolar experiences and how did the podcast come about?

I’ve always tried to be an advocate for folks who struggle with their mental health, particularly those with bipolar disorder. Most of the time no one knows that I have a serious mental-health disorder, so I feel both able to and obligated to speak out. I also want folks to see that someone with a major mental-health disorder can live well with this illness.

Ghandi said that the true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members. People struggling with mental illness are definitely vulnerable, especially to stigma. There are exceptional groups with exceptional folks like Dr. Erin Michalak and the team at CRESTBD out of the University of British Columbia that are working to improve care for individuals with lived-experience with bipolar disorder in Canada and globally. I’m thankful to CRESTBD for helping me bring a message of hope to the broader community of folks with bipolar disorder as well as their supports.

Along with its other functions, astrocytes are said to play a part in mental health. Did this play a part in your research?

My research focused on individual cells rather than whole brains, but I love learning about how astrocytes’ roles in complex brain phenomenon continues to be uncovered. Understanding that astrocytes are involved in complex brain function also indicates that they’re likely involved in disorders of our brains too. Astrocytes, or disruptions in astrocyte function, have been shown to be implicated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer’s, epilepsy and mental health, among others. Astrocytes are integral to how brains function, and given that mental health disorders are brain disorders it wasn’t surprising to me that they’re involved.

What is the best way to support someone with bipolar disorder?

As a start, always begin from a place of kindness, thoughtfulness and respect.

When a person is well it’s easier to ask them how they’re doing, and importantly to ask them what they’d like you to do and listen to their requests without judgement. Together, you can build support plans including building a team of supports (peer support, psychologist, and psychiatrist) around them to help manage their illness if their mood destabilizes.

When someone with bipolar is hypomanic it’s a good time to get them to seek medical attention from their psychiatrist and psychologist. Implementing early interventions: medication, a better sleep routine, attempts to decrease stress and decreased stimulating environments are especially important. But again, offer kind and supportive help, ask what they need from you — rather than telling them.

Definitely don’t argue with someone who’s mood is becoming unstable! I’ve explained bipolar disorder to some folks as like relapsing and remitting MS. Most of the time I’m well, but there are times due to the nature of my illness that accommodations are necessary so that my mood does not deteriorate further.

How do you assist someone during a mood episode?

How to help someone in the midst of a major mood episode can be really tricky. If someone is bipolar and they’re having either a major manic or depressive episode, they need medical attention as soon as possible. I’ve described the need for medical assistance as akin to someone having an epileptic seizure. There’s evidence that major episodes can affect someone’s brain long-term, so seeking help is crucial. This is true for both depressive episodes and mania.

The problem is that people in the midst of these episodes lose something called insight. Insight is where the individual knows that something is wrong and that they need to seek help. During my first episode I had no idea of the danger I was in, nor the severity of the episode. This is when it’s important to get someone to the hospital. While that seems harsh, imagine you were coming across someone who was having a heart attack, epileptic seizure or diabetic shock. You would call an ambulance.

The problem with mental-health crises is that there is so much stigma around them that there aren’t great systems in place to get someone the help they need. More funding and awareness is needed. Bell “Let’s Talk” Day, among other initiatives, isn’t enough. The funding for mental health in Calgary is woefully insufficient for the number of individuals that need care. It can be a two-year wait for individuals to get to see a psychiatrist. Mental-health care is something that everyone should fight for.

How do you learn to take care of yourself first?

At times this can be really hard, especially because I’m both a mom and a partner as well as a professor and neuroscientist. I have learned over the years that if I’m not well I can’t be any of the roles that I cherish. Self-care is such a buzz word these days but there are things I do every day to stay well. These include living a more regimented life, taking medication, getting outside and exercising, and being patient and kind to myself.

Have there been any things that you feel are positive outcomes of your lived-experience with bipolar disorder?

I think having bipolar disorder has taught me to have deep empathy for those who struggle with their mental health or other chronic conditions. The dramatic onset of my illness has left me so grateful for the things that I’ve achieved in spite of, but also because of my lived-experience with bipolar disorder. I value my relationships, not just with my partner but also with my children, friends and supportive colleagues. Knowing that I can be a strong advocate for those with lived-experience is also something that I’m immensely proud of and thankful for.

For mental-health assistance in Calgary, call

Access Mental Health at 403.943.1500,

Distress Centre Calgary at 403.266.4357, or the

Mental Health Help Line at 1.877.303.2642.